Walk into any modern supermarket today, and you will find rows upon rows dedicated to brightly packaged drinks, instant noodles, potato chips, and ready-to-eat foods, promising convenience. Convenience has reshaped how we eat, but that ease has come with a cost.

For the last four decades, the consequences have become apparent. As ultra-processed foods have become more widespread globally, so have rates of obesity, non-communicable diseases, and chronic inflammation. According to the World Health Organisation, obesity has nearly tripled worldwide since 1975, while the prevalence of type 2 diabetes has risen sharply across both developed and developing nations. One key culprit? Our changing relationship with food.

What Science Says About the Issue

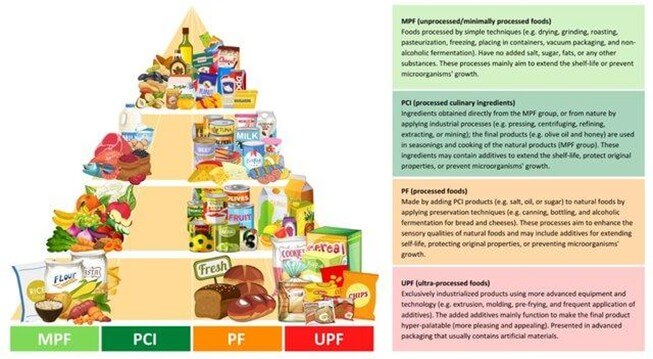

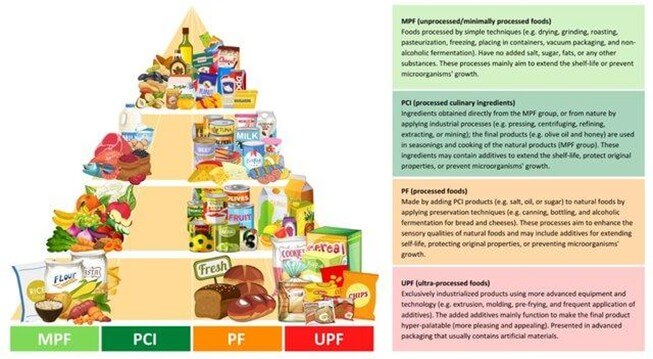

In the late 2000s, researchers at Brazil’s Centre for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition (NUPENS) released a commentary containing a groundbreaking discovery: the nature of the food and the nutrients it contained weren’t as problematic as the processing. In essence, it wasn’t just what people ate, but how their food was made that mattered. The discovery of this crucial pattern led to the development of the NOVA food classification system, which categorises foods not by nutrients alone but by the degree and purpose of industrial processing—a shift that transformed modern nutrition science (Monteiro et al., 2018).

What Makes Ultra-Processed Foods Harmful?

Before we delve into any cons, it is important to gain an initial understanding of the topic at hand. To this effect, UPFs are products that have undergone a series of industrial processes, including but not limited to extrusion, pre-frying, fractioning, and chemical modification (Monteiro et al., 2019). These processes, coupled with the use of additives such as colourings, emulsifiers, and preservatives, fundamentally alter the ingredients’ food structure (Al Marshad et al, 2022). While the result may be inexpensive and hyper-palatable products with an extended shelf life, these types of food could offer an unhealthy proposition for the consumer. They often contain emulsifiers, stabilisers, artificial flavours, sweeteners, and preservatives that one would not find in a home kitchen. In an Australian cross-sectional study, UPF products were found to contain 4.7, 2.9, and 1.9 times more free sugars, sodium, and energy density, respectively, and 1.7 and 1.4 times less potassium and fibre, respectively, than non-ultra-processed products (Muchado et al, 2019)

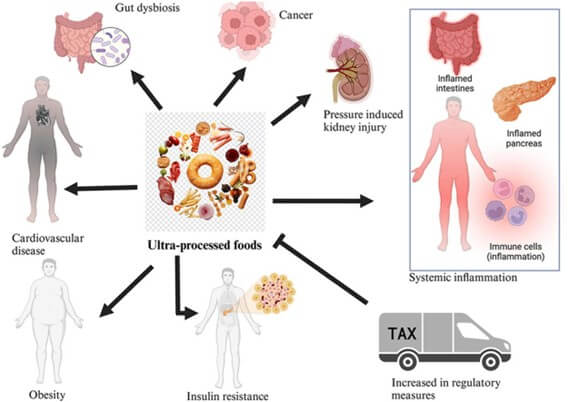

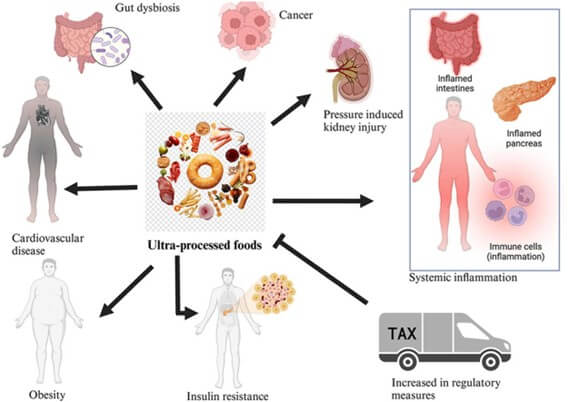

What happens when someone keeps consuming UPFs? Large-scale population studies have illustrated several consequences, such as increased risks of:

- Obesity and overeating, which are driven by low fibre content and disrupted satiety signalling – your body’s natural ‘fullness’ signals. When someone regularly eats UPFs, this natural process is thrown into disarray. In fact, in one controlled study, people eating ultra-processed diets consumed about 500 extra calories per day without realising it (Hall et al., 2019)

- Gut microbiome disruption and inflammation. Food additives and lack of fermentable fibre slow down beneficial gut bacteria growth (Zinöcker & Lindseth, 2018)

- Cardiovascular diseases, cancers, hypertension and type 2 diabetes. According to Babalola et al (2025), the consumption of UPFs has been significantly associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and various types of cancer, along with hypertension and type 2 diabetes, particularly in rapidly urbanising regions (Srour et al., 2020). The increased consumption of UPFs can result in a deficiency of essential nutrients, impairing the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis and potentially leading to defective immune surveillance. This dysfunction has been well-documented across various cancer types and represents a plausible mechanistic link between UPF intake and carcinogenesis (Kliemann et al., 2022 in Balabolola et al 2025). Signalling pathways linked to insulin and leptin are being studied as possible causes of tumour development in breast cancer, where obesity and overweight are recognised risk factors (Ghasemi et al., 2019 in Babalola et al 2025).

- Depression and anxiety. Growing evidence is linking poor diet quality to mental health outcomes (Lane et al., 2023)

What makes this particularly concerning is that these associations persist even when calorie intake is controlled. It is not just about eating too much — it is about what processed food does to your body at a cellular level. The processing itself matters, not just the nutrients listed on a label (Monteiro et al., 2018).

Dr Chris van Tulleken, an infectious disease doctor and associate professor at University College London, puts it bluntly in his book Ultra-Processed People: these aren’t really foods at all, but “industrially produced edible substances” engineered for profit, shelf life, and hyper-palatability – not for human biology.

A Global Nutrition Transition

Countries around the world are experiencing what public health experts call a “nutrition transition”—moving from traditional diets centred on whole foods toward increasingly processed, Westernised eating patterns. This shift looks different in different places, but the trajectory is remarkably similar.

Consider a typical urban professional’s day, then versus now:

A generation ago, our Sri Lankan grandparents used to consume string hoppers with kiri hodi for breakfast and rice and curry for lunch. In Germany, the alternative may have been hot porridge in the morning, with grilled meat and steamed vegetables for lunch/dinner. Their meals were often home-cooked or prepared fresh. Drinks were mostly water, coffee/tea, or fresh juice.

Today: We might stop by a bakery and buy a packaged muffin or pour processed cereal with milk and drink instant coffee for breakfast, order fast food or pre-made meals for lunch, consume artificially flavoured fizzy drinks at our gatherings and eat instant noodles for dinner.

The shift is subtle but significant. We are trading foods our grandparents would recognise for industrial products they would not. And this is happening in both the developed and developing world.

In tropical regions, particularly, where fresh fruit has traditionally been abundant and accessible year-round, this transition feels especially ironic. Why reach for artificially flavoured “tropical fruit punch” when mangoes, papayas, and pineapples grow in abundance?

Why Simple, Minimally Processed Smoothies Matter

As ultra-processed foods take over the world’s stores, minimally processed foods become increasingly rare. This is where the topic becomes more practical for current consumers. Smoothies prepared from whole or gently processed ingredients provide a healthier option for those looking for convenience without compromising on nutrition. However, not all smoothie beverages are created equal. A typical commercial “fruit drink” may contain only 5-10% genuine fruit, whereas 90% of it is comprised of added sugars, artificial colours (with chemical codes), such as E110 or E102, synthetic flavours, preservatives, and thickening agents. The label may even mention 20 or more ingredients, most of which you cannot pronounce!

The Nootz Approach: Tropical Simplicity

This is where Nootz enters the picture — not as another processed beverage, but as a deliberate rejection of ultra-processing, rooted in the abundance of tropical ingredients.

Let’s be clear about what happens to make Nootz smoothies:

- Sourcing: Fresh tropical fruit is sourced from our Sri Lankan farms

- Simple preparation: Fruit is pureed, and coconut water and milk are extracted

- Blending: Ingredients are combined

- Minimal preservation: Flash pasteurisation and cooling — processes that preserve safety without adding chemicals

- Packaging: Sealed for freshness

Compare this to what happens in ultra-processing: ingredient fractioning (isolating proteins and starches), chemical modification (hydrogenation, acid treatment), synthesising flavours and colours, and adding multiple emulsifiers and stabilisers

Take Mango Nootz as an example. The ingredient list reads like a simple kitchen recipe: coconut milk, mango puree, and coconut water. That is it. No stabilisers with cryptic E-numbers. No “nature-identical flavouring substances”. No colours requiring regulatory disclaimers.

Or consider Passion Fruit Nootz — made with actual passion fruit puree, not passion fruit “flavouring” synthesised in a lab. You can taste the difference because you are tasting the real fruit, complete with its natural acidity and subtle complexity.

Papaya Nootz offers another example of simplicity. Papaya is one of the tropics’ most accessible fruits — but turning fresh papaya into a convenient, ready-to-drink smoothie at home means cutting, deseeding, blending, and cleaning up. Nootz does this minimal processing for you, then stops. No additives needed. No shelf-life extenders. Just papaya, coconut, lime and a tinge of low-GI coconut sugar.

The same philosophy applies to Pineapple Nootz—real pineapple puree that retains the fruit’s natural enzymes and fibre, rather than pineapple “extract” or “concentrate” that requires binding agents and high heat processing

This sits firmly at the minimally processed end of the NOVA spectrum (NOVA Group 3, to be precise — processed foods made recognisable from their original ingredients, not ultra-processed formulations).

Convenience Does Not Have To Come At A Cost

The rise of ultra-processed foods was driven by convenience, and that convenience genuinely matters. Parents rushing kids to school, professionals working long hours, students cramming for exams — everyone needs options that do notrequire extensive time in the kitchen.

But science now makes one thing clear: convenience does not need to come at the cost of health.

When you grab a Nootz Mango smoothie from the fridge instead of a packaged “health drink” loaded with added sugars and stabilisers, you are making a conscious choice. When you reach for Pineapple Nootz instead of an artificially flavoured soda, you are voting with your wallet for a different kind of food system.

These are not perfect choices — no processed food is the nutritional equivalent of a home-cooked meal made from scratch. But they are dramatically better choices within the reality of modern life. They help reduce UPF intake, support gut and metabolic health, and reconnect our diets with real food.

What Would Your Grandmother Recognise? The Return to Real Ingredients

When we choose simple foods made from simple ingredients, we acknowledge age-old food wisdom. Traditional diets around the world—whether Mediterranean, Asian, Latin American, or others—have always been built on a foundation of simplicity: whole grains, fresh vegetables, quality proteins, seasonal fruits, minimal processing. Our grandparents didn’t need nutrition labels to eat well because they were eating food, not food products.

At Nootz, we symbolise a return to this philosophy, but with a contemporary twist. It is a new model of convenience: one rooted in simplicity, transparency, and nourishment rather than ultra-processing. Our ingredients are foods your grandmother would recognise, even if the packaging is modern. Our flavours come from real tropical fruits that have nourished communities for generations. The processing is minimal—just enough to make whole foods convenient, not so much that they stop being whole foods.

In a global market flooded with ultra-processed options, that is not just refreshing; it’s revolutionary.

References

Almarshad, M. I., Algonaiman, R., Alharbi, H. F., Almujaydil, M. S., & Barakat, H. (2022). Relationship between ultra-processed food consumption and risk of diabetes mellitus: A mini review. Nutrients, 14(12), 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122366

Babalola, O. O., et al. (2025). The impact of ultra-processed foods on cardiovascular diseases and cancer: Epidemiological and mechanistic insights. Aspects of Molecular Medicine, 5, 100072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amolm.2025.100072

Fardet, A., & Rock, E. (2018). Reductionist nutrition research has meaning only within the framework of holistic and ethical thinking. Nutrition Reviews.

Hall, K. D., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain. Cell Metabolism.

Lane, M. M., et al. (2023). Ultra-processed food consumption and mental health outcomes. Public Health Nutrition.

Machado, P. P., Steele, E. M., Levy, R. B., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed foods and recommended intake levels of nutrients linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 9, e029544. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029544

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., et al. (2018). The NOVA classification system and the definition of ultra-processed foods. Public Health Nutrition.

Monteiro, C. A., et al. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition.

Rosier, C. L., et al. (2025). From soil to health: advancing regenerative agriculture for improved food quality and nutrition security. Frontiers in Nutrition.

Srour, B., et al. (2020). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease. BMJ.

Zinöcker, M. K., & Lindseth, I. A. (2018). The Western diet–microbiome–host interaction and its role in metabolic disease. Nutrients.

January 29, 2026